Tom Burrell was born in 1939 and he grew up on Chicago’s South Side. When he entered the advertising agency business in 1961, he was the only black person in the entire city of Chicago working in the field. To say that Burrell is a maverick is too tame. He’s a trailblazer who climbed the highest mountains in American business and then learned to thrive in that thin white air.

Burrell began his career in advertising while still attending Chicago’s Roosevelt University, where he graduated with a B.A. in English. His first job was in the mailroom at Wade Advertising. He wore a suit to work every day because he wanted to signal that he belonged at the agency but not in the mailroom. “My strategy was to look and comport myself as if I didn’t belong in the mailroom,” he said. “I walked around looking like an executive even as I changed the towels in the towel machine and changed the Cokes in the Coke machine and ran errands. That way, when it was time for me to make a move, it didn’t meet with incredulity.”

Burrell quickly worked his way from the mailroom into the position of Junior Copywriter assigned to the agency’s Robin Hood All-Purpose Flour and Alka-Seltzer accounts. He recalls, “I had no contact with the client. It was radical enough for a black person to be working in an agency. Presenting that person to a client was another three or four steps ahead.”

From there, he went on to work as a copywriter at Leo Burnett, Foote, Cone & Belding, and Needham, Harper & Steers before launching Burrell McBain Advertising in 1971.

Burrell’s Black Consciousness

Tom Burrell came of age during the civil rights movement, which was led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. The main idea at the time was integration. But Burrell understood that assimilation into the white culture was never the desired end. With the rise of black nationalism and black pride in the late 1960s, the door cracked opened and he began producing ads that were aimed at black people and that incorporated elements of black culture.

Burrell used the power tools that he had in his toolbox. He isn’t an organizer or speech giver. He is a mass communicator seeking to change the public discourse.

“I had to convince clients to understand that black people are not dark-skinned white people,” Burrell explained. “Sometimes when you start talking to people about race and differences, implied in that is some kind of subordination, so I had to convince them that you can be different and equal and that there are cultural differences that should be part of advertising aimed at a black cultural group, such as music.”

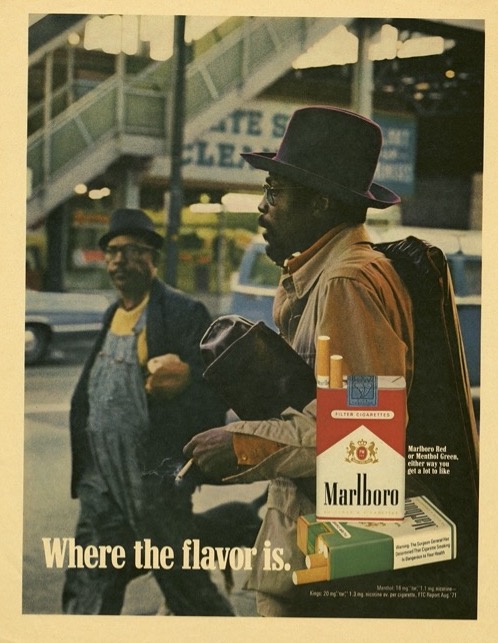

When Marlboro Wasn’t the Man

Burrell’s new agency first attracted notice with a national campaign for Marlboro. “Marlboro ads had a line, ‘Come to where the flavor is,’ and it was all about white cowboys – talk about a stretch,” Burrell recalled. “So we chopped off ‘Come to,’ and that referred to the cool way of saying this is where the cultural flavor, the richness, is in the black community. We got rid of the cowboy and we had the coolest guys that we could come up with going through their daily activities, smoking. That was huge.”

Network TV for McDonald’s and Coca-Cola

Replacing the Marlboro Man with urban black men was a big win for Burrell. A win that helped bring McDonald’s and Coca-Cola—two of the world’s largest advertisers—to his agency. Network television ads offered unique visibility and influence to Burrell Communications. A collection of Burrell’s Advertisements for Coca-Cola is now archived at the Library of Congress for its cultural and historical significance.

For McDonald’s, Burrell positioned the company as a safe and inviting place for black people to eat, gather, and work. Maybe that does not sound like much today, but in the early 1970s, it meant a lot. Many public schools in the South were still segregated, along with the rest of American society.

When viewed through today’s cultural lenses, the “Calvin” ad for McD’s may appear condescending. The Coca-Cola ad too could be faulted for trading in one stereotype just to replace it with another. Both ads depict black people chillin’ on the front steps of a Chicago home and on the street corner. In the Coke ad, it’s mostly a good thing. In the McDonald’s ad, which appeared 12 years later, it’s not.

“Calvin,” the hero of the McDonald’s spot is the good citizen who learns responsibility on the job. Even by 1990 standards, it seems like this ad was made to attract some while repelling others. One can also see Burrell’s focus on self-respect and gaining respect for black people in this ad. Nevertheless, when you make a hero of the young man because he has a job at McDonald’s, must you also portray the young men with no such job as somehow less than?

The adman in me says we’re not here to solve societal ills, we’re here to help our clients sell. But, Burrell was on a mission with respect for black people at its core, so why throw shade on the young men with no job? Was it just good advertising, or was it good advertising with a socially conservative message?

Burrell’s work reminds me of Ad Legend Mary Wells Lawrence who made sexy commercials for Braniff Airlines, resurrecting the airline in the process. But her spot, “Airstrip,” would never be made today. Maybe the “Calvin” ad would not be made either. The question for the advertising student is, “How effective were these ads at the time?” The answer is they were incredibly effective. Mary Wells Lawrence gave businessmen a compelling reason to fly. Burrell gave corporate America a lesson in respecting black people while making ads for black people, which increased the visibility of black people in the media in a big way.

And he, like Mary Wells, became rich, famous, and powerful in the process.

Let’s Hear Directly from Tom

Tom Burrell is a fighter and success hasn’t dimmed the fire in his belly. Let’s listen…

In the video above, Burrell talks about “Positive Realism” and how his agency used it to depict real scenes from black peoples’ lives. He also says he was a pretty good cultural anthropologist. To prove it, he says, “In the black community, McDonald’s was a feeding station. We had no dinner time ritual. So there was no big bump at 6:00 p.m.”

Burrell also says, “There’s no such thing as the general market. If you’re not targeting, you’re not marketing.” Ad Legends, David Ogilvy, Rosser Reeves, and Lester Wunderman would all wholeheartedly agree.

He’s Motivated, Intelligent, and Fierce

Tom Burrell’s father asked him, “What makes you think you can go to college?” When Burrell was in college a well-meaning professor asked him, “What makes you think you can get into the advertising business?” Burrell was highly motivated to prove his father and the professor wrong, and he was clearly up to the challenge.

What else was driving him to climb the ad industry mountain? “My primary interest was not in advertising, Burrell says. “My interest was in persuasive communications, and the psychology of it. All the major institutions are about persuasive communications. Whether you’re talking about government, religion, or higher education. Of those, advertising is the purest form of persuasive communications because it makes less pretense about what its purpose is.”

In describing the industry, Burrell could be describing himself, for there are zero pretenses about this man and no confusion at all about his primary objectives in life. He’s about uplift for himself and the many people who have worked with him and for him, and also for the millions of people in the audience that he and his team were able to reach.

Tom Burrell’s Amazing Legacy

After “re-wiring” in 2004, Burrell became an author and lecturer focusing on media, pop culture, social sciences, and American history. His book, Brainwashed: Challenging the Myth of Black Inferiority, continues to spark lively conversation on the powerful role media messaging plays in affecting race-related attitudes and behavior.

Here’s ABC-7 in Chicago just last year, looking back on the man’s incredible legacy.

Burrell also founded the nonprofit Resolution Project to “challenge and reverse ongoing mass media stereotypes and negative race-based conditioning.” Facing centuries of oppression plus a modern onslaught of negative portrayals of black people in media, Burrell battled ignorance and lethargy and he won.

He found inspiration in the Black Power movement and used this inspiration to fuel his dream. As an adman, Burrell understood the power of images to shape culture and opinions. He also realized the depth and size of the African-American market. At the same time, he knew how to convince big brands to target this market with general market TV ads, which not incidentally, also moved the white people in the audience to like the brands more.

It is incredible to realize how much Tom Burrell achieved. Burrell injected “Positive Realism” into the culture, and by so doing, he pushed other more harmful images and narratives about black people out of the frame, while replacing them with strong characters, who are uniquely American and yet collectively bound by the terrible history of slavery and the ongoing legacy of racism.

Burrell also convinced white Americans and the men who run its most powerful companies that they could either learn to respect black people or stand no chance of selling them a damn thing. He is one of the ad industry’s all-time great change agents and most legendary figures.